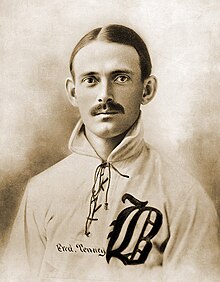

Fred Tenney

| Fred Tenney | |

|---|---|

| |

| First baseman / Manager | |

| Born: November 26, 1871 Georgetown, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| Died: July 3, 1952 (aged 80) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 16, 1894, for the Boston Beaneaters | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 7, 1911, for the Boston Rustlers | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .294 |

| Hits | 2,231 |

| Home runs | 22 |

| Runs batted in | 688 |

| Managerial record | 202–402 |

| Winning % | .334 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| As player

As manager | |

Frederick Tenney (November 26, 1871 – July 3, 1952) was an American professional baseball player whose career spanned 20 seasons, 17 of which were spent with the Major League Baseball (MLB) Boston Beaneaters/Doves/Rustlers (1894–1907, 1911) and the New York Giants (1908–1909). Described as "one of the best defensive first basemen of all time", Tenney is credited with originating the 3-6-3 double play and originating the style of playing off the first base foul line and deep, as modern first basemen do.[1][2] Over his career, Tenney compiled a batting average of .294, 1,278 runs scored, 2,231 hits, 22 home runs, and 688 runs batted in (RBI) in 1,994 games played.

Born in Georgetown, Massachusetts, Tenney was one of the first players to enter the league after graduating college, where he served as a left-handed catcher for Brown University. Signing with the Beaneaters, Tenney spent the next 14 seasons with the team, including a three-year managerial stint from 1905 to 1907. In December 1907 Tenney was traded to the Giants as a part of an eight-man deal; after two years playing for New York, he re-signed with the Boston club, where he played for and managed the team in 1911. After retiring from baseball, Tenney worked for the Equitable Life Insurance Society before his death in Boston on July 3, 1952.

Early life

[edit]Tenney was born in Georgetown, Massachusetts, the third of five children to Charles William and Sarah Lambert (née DeBacon) Tenney.[3] Charles Tenney attended Dummer Academy from 1850 to 1853, and served for the 50th Massachusetts Regiment in the Civil War, where he nearly died due to "intense suffering".[3] Growing up, Fred led his class in drawing and sketching.[4] He reportedly started playing baseball around 1880.[5]

Career

[edit]Brown University

[edit]In 1892, Tenney played his first professional game for the Binghamton Bingos of the Eastern League, going 1 for 4 with a single.[6] He played as Brown University's catcher for the 1893 and 1894 seasons. In 1894, the team had a 23–8 record and were selected as national champions by Harper's Weekly.[7] The night of his senior dinner, Tenney received a telephone message from Frank Selee, the manager of the Beaneaters, asking him to play a game for the team at catcher, due to the injuries of other players.[7][8]

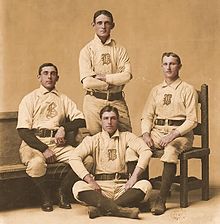

Boston

[edit]

In his MLB debut on June 16, 1894, Tenney had to be removed from the game in the fifth inning due to a fractured finger on his throwing hand from a foul tip. After Tenney had his finger addressed, James Billings, an owner of the Beaneaters, offered him a contract worth US$300 a month from that day.[9] Tenney, later writing about the day, stated:

I thought they were trying to have a little joke with me, and I concluded that I could do a little kidding myself. So I thought I would call their bluff by asking for some advance money. I screwed up my courage and asked Mr. Billings whether, if I signed the contract at once, I could get some advance money. He asked how much I wanted, and I thought I would mention a big sum in order to call their bluff good and strong. So I said $150. He consulted with Mr. Conant, another Director, and said that I could have the money all right, and asked me how I would like to have it– cash or check. [...] I replied that I would take half cash and then half in check, and immediately he wrote out a check for $75, counted out $75 in cash, shoved the contract over to me to sign, laying the cash and check beside it.

— Fred Tenney, The New York Times[9]

He returned to the team a month later, and finished the year batting .395 in 27 games.[8] The following season, Tenney moved to the outfield due to an erratic throwing arm behind the plate, according to manager Selee.[8] For the season, he hit .272 in 49 games, while also playing minor league baseball for the New Bedford Whalers. In 1896, Tenney again caught and played outfield; offensively, however, Tenney hit .336 in nearly double the games from the previous year (88) despite playing in the minors for the Springfield Ponies.[10]

In 1897, Tenney moved to first base to replace the aging Tom Tucker. According to Alfred Henry Spink, within two weeks of the move it was evident that Tenney had become "one of the finest first sackers that the game [had] ever seen."[11] On June 14, 1897, in a game against the Cincinnati Reds, Tenney turned the first 3-6-3 double play in MLB history.[12] Offensively, Tenney led MLB in plate appearances (646) and tied Duff Cooley, Gene DeMontreville, and George Van Haltren for the lead in at bats (566) as the Boston club became National League (NL) champions with a 93–39 record.[13][14]

Boston again won the NL in 1898 while Tenney hit .328 with 62 RBIs. In 1899 he collected 209 hits, fifth most in MLB, and recorded 17 triples, good for fourth best in MLB.[15] In 1900 Tenney, at age 28, batted .279 over 112 games played.[16] He began a streak of seven consecutive seasons where he led the NL in assists in 1901; he holds the record for most seasons leading a league in assists, with eight, including one in 1899.[1] He was suspended for ten games for fighting Pittsburgh Pirates manager Fred Clarke in May 1902,[8][17] and finished the 1902 season with the second most sacrifice hits (29) in the majors, to go along with a .315 average.[10][18] Throughout the 1901–1902 seasons, Tenney received contract offers worth up to $7,000 ($206,248 in 2017) from St. Louis, Cleveland, and Detroit;[8] Tenney, however, decided to remain in Boston, and was named captain of the club in 1903.[1] For the season, he hit .313, with 41 RBIs and three home runs, as he led his team in walks (70) and had the best on-base percentage mark (.415) on the squad.[19] In 1904, Tenney again led his team in walks and on-base percentage, as he tied for the team lead in runs with Ed Abbaticchio.[20]

He was named manager of the team in 1905, but did not receive additional pay; he was, however, offered a bonus if the team didn't lose money.[8] In 1905, Tenney tried to sign William Clarence Matthews, an African-American middle infielder from Harvard University, to a contract. Tenney later retracted his offer due to pressure from MLB players.[21] Defensively, he led the majors in errors committed by a first baseman and finished second in most putouts for any position.[22] Tenney led the 1906 Beaneaters to a 49–102 record. For the second straight year, the Boston team lost more than 100 games.[23]

After a 158–295 record as manager, on December 3, 1907, Tenney was traded to the Giants, along with Al Bridwell and Tom Needham, for Frank Bowerman, George Browne, Bill Dahlen, Cecil Ferguson and Dan McGann;[10] the trade was called "one of the biggest deals in the history of National League baseball".[24]

New York Giants

[edit]

In his first season with the Giants, Tenney led MLB with 684 plate appearances and finished third in runs scored, with 101.[25] In a game against the Chicago Cubs on September 23, Tenney could not play due to an attack of lumbago; it was the only game he did not play in during the season.[26] Rookie Fred Merkle took his spot at first base. The game was at a 1–1 tie in the bottom of the ninth. Merkle, after hitting a single, was at first, and Moose McCormick was at third, with two outs. Al Bridwell singled to center field, but Hank O'Day called Merkle out because Merkle had not touched second base.[26] O'Day ruled the game a 1–1 tie due to darkness.[26] With both teams finishing the season at a 98–55 record, a replay game had to be played to determine who would win the National League pennant. The game was held on October 8, with the Cubs winning, 4–2.[26]

After batting a career low .235 in 1909, Tenney was released by the Giants.[8][27] He spent the 1910 season as a player–manager for the minor league Lowell Tigers, leading the team to a 65–57 record, good for fourth (out of eight teams) in the New England League.[28]

Return to Boston

[edit]On December 19, 1910, Tenney signed a two-year contract with the Boston Rustlers. For the 1911 season, Tenney hit .263 over 102 games.[10] He was released by the Braves on March 20, 1912, after 44–107 record in one season; Tenney was paid not to manage for the second year on his contract.[8]

In 1916, he bought the Newark Indians of the International League with James R. Price for $25,000 ($527,450 in 2012).[29][30] Mayor Thomas Lynch Raymond declared April 27 a "half-holiday" for the city of Newark for the Indians' Opening Day.[31] Tenney played in 16 games for the Indians, hitting .318 with seven hits over 22 at-bats, and managed the team to a 52–87 record.[32][33]

Personal life and death

[edit]Tenney married a Georgetown girl, Bessie Farnham Berry, on October 21, 1895. The couple had two children together; Barbara, born July 4, 1899, and Ruth, born December 8, 1901.[3] Early in his career, he refused to play baseball on Sundays due to his religion,[3] although he later changed his mind.[34] Tenney was known as the "Soiled Collegian" at the major league level because it was unpopular for college players to become professional.[35] Tenney served as a journalist for The Boston Post, Baseball Magazine, and The New York Times.[8] He painted and sketched during the winter.[4]

After retiring from baseball, Tenney worked for the Equitable Life Insurance Society and continued writing for The New York Times. In 1912, he was vice-president of the Usher–Stoughton shoe manufacturing company in Lynn, Massachusetts; later, he formed the Tenney–Spinney Shoe Company in partnership with Henry Spinney.[36][37] He was balloted for the National Baseball Hall of Fame from 1936 to 1942 and again in 1946, but never received more than eight votes, receiving eight (3.1% of total ballots cast) during the Baseball Hall of Fame balloting in 1938.[10] Tenney died on July 3, 1952, at Massachusetts General Hospital after a long illness.[8][35] He was interred at Harmony Chapel and Cemetery in Georgetown.[10]

In 2023, Tenney was posthumously inducted into the Braves Hall of Fame, alongside Rico Carty.[38]

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of Major League Baseball single-game hits leaders

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Caruso, Gary (1995). Braves Encyclopedia. Temple University Press. pp. 30, 245. ISBN 978-1-56639-384-3.

- ^ Porter, David L. G. (2000). Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Q–Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1528. ISBN 978-0-313-31176-5.

- ^ a b c d Tenney, Jonathan; Tenney, Martha Jane (1904). The Tenney family, or, The descendants of Thomas Tenney of Rowley, Massachusetts, 1638–1904. Rumford Press. pp. 539–540, 613–614.

- ^ a b "Fred Tenney is an Artist; The Famous ball player is a Clever Painter and Sketcher". The Pittsburg Press. March 31, 1905. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Hern, Gary (1951). "Tenney, Edison of the First Sack". Baseball Digest. 10 (3). Lakeside Publishing Company: 43–45.

- ^ "1892 Binghamton Bingos". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Harris, Rick (2012). Brown University Baseball: A Legacy of the Game. The History Press. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-1-60949-501-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sternman, Mark. "Fred Tenney". The Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Tenney, Fred (March 21, 1910). "How Tenney Broke into Baseball; Thought Boston Managers Were Joking When They Offered Him Money to Play" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fred Tenney". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ Spink, Alfred Henry (1911). The National Game. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8093-2304-3.

- ^ Morris, Peter (2010). A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-56663-853-1.

- ^ "1897 Major League Baseball Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "1897 Boston Beaneaters". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "1899 Major League Baseball Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "1900 Boston Beaneaters". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Players Punished" (PDF). Sporting Life. 39 (10): 1. May 24, 1902. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "1902 Major League Baseball Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "1903 Boston Beaneaters". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "1904 Boston Beaneaters". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Tierney, John P. (2008). Jack Coombs: A Life in Baseball. McFarland. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7864-3959-1.

- ^ "1905 Major League Baseball Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves Team History and Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Fleming, Gordon H. (2006). The Unforgettable Season. University of Nebraska Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8032-6922-4.

- ^ "1908 Major League Baseball Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Girsch, George (1958). "Was it really Bonehead Merkle– or Bonehead O'Day?". Baseball Digest. 17 (9). Lakeside Publishing Company: 41–48.

- ^ "Fred Tenney Handed his Unconditional Release". The Sunday Tribune. May 10, 1910. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ "New Bedford Wins Pennant" (PDF). The New York Times. September 11, 1910. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Chadwick, Henry; Foster, John Buckingham; White, Charles D. (1916). Spalding's official base ball record. American Sports Publishing Co. p. 5.

- ^ "Jersey City Club Sold: James R. Price and Fred Tenney Buy International Franchise" (PDF). The New York Times. February 19, 1916. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Tenney's Men Start Today: Mayor of Newark Declares Half-Holiday for Opening" (PDF). The New York Times. April 27, 1916. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "1916 Newark Indians". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ Wright, Marshall D. (1998). The International League: year-by-year statistics, 1884–1953. McFarland. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7864-0458-2.

- ^ "Tenney to play Sunday ball". The Pittsburgh Press. December 23, 1906. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Fred Tenney, Creater of 6-3-6 Double Play, Taken by Death". Lewiston Morning Tribune. July 4, 1952. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ "Fred Tenney in Shoe Business" (PDF). The New York Times. June 1, 1912. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ American shoemaking, Volume 51. Mcleish Communications. 1914. p. 595.

- ^ Bowman, Mark (August 18, 2023). "Carty, Tenney to enter Braves Hall of Fame". MLB.com. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- 1871 births

- 1952 deaths

- Major League Baseball first basemen

- Major League Baseball player-managers

- Boston Beaneaters players

- Boston Doves players

- New York Giants (baseball) players

- Boston Rustlers players

- Boston Beaneaters managers

- Boston Doves managers

- Boston Rustlers managers

- Minor league baseball managers

- Lowell Tigers players

- Newark Indians players

- Binghamton Bingos players

- Springfield Ponies players

- Brown University alumni

- People from Georgetown, Massachusetts

- 19th-century baseball players

- The Governor's Academy alumni

- Baseball players from Essex County, Massachusetts

- The Boston Post people

- New Bedford Whalers (baseball) players

- Pawtucket (minor league baseball) players